“Satire lets you laugh so that you can finally look”: An Interview with Emily Mitchell

by Alexia Woodall

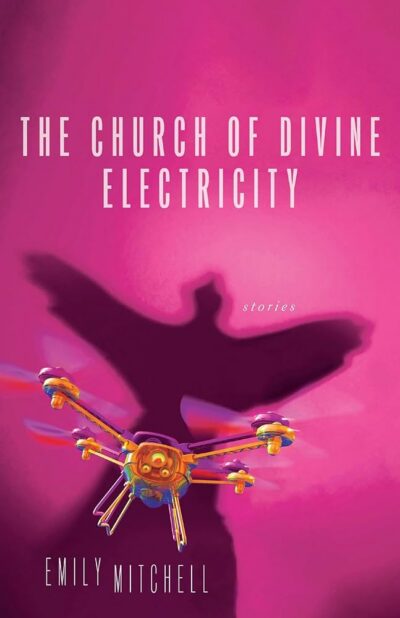

Prairie Schooner Graduate Research Assistant Alexia Woodall recently spoke to Emily Mitchell about her newest publication, The Church of Divine Electricity, winner of the 2023 Elixir Press Fiction Prize. She is the author of two other books, The Last Summer of the World: A Novel and Viral: Stories. Her second novel, Far Ocean, won the 2025 Big Moose Prize and is forthcoming from Black Lawrence Press in 2027.

Alexia Woodall: Where did the idea for this collection come from? Did it start from one specific story?

Emily Mitchell: The very first story I wrote in the collection is actually one that comes quite late in the book, which is “In Which I Try to Save the World From Total Destruction Through the Power of Art.”I was thinking about how it might be possible to look at contemporary human beings, especially American human beings, from an outsider’s point of view, to step back and not take for granted the things that we tend to take for granted about our lives.

The epigraph for the entire collection comes from Robert Hayden’s poem “[American Journal]”, which is written from the point of view of an alien ambassador who comes to earth and is looking around, trying to figure out what is going on with these strange people who surround him. The idea for the story came out of reading that poem. In my story, unlike in Hayden’s poem, the alien visitor has also been sent to judge our worthiness to survive. How would we try to demonstrate that? Obviously we can’t because we aren’t worthy, we’re wonderful and terrible in just about equal measure and you have to take our value as axiomatic. Human beings are all absolutely precious, deserving of continuity and peace. Nothing that we could do could ever possibly justify our existence but also we shouldn’t have to try. That was the story that I wrote first, and then the others came out one by one over about ten years.

AW: I found that many of the stories involved transformation in the physical, emotional, or spiritual sense. What inspired you to use metamorphosis as a running motif?

EM: Having a body is strange and amazing. One of the less acknowledged parts of human life is the degree to which, over the course of our lives, our bodies continually change and remake themselves, even on a cellular level. We like to think of the body as this stable thing but of course it’s not. There are cultural pressures that tell us the body shouldn’t age, it shouldn’t change size or shape, should conform to certain narrow and rigid ideals. Politically, right now, there are forces in the culture that say you shouldn’t change your body in certain ways to do with gender expression, even if it feels necessary and urgent to do so. For me, writing about the body transforming radically or magically is a way of reflecting on the degree to which our bodies already transform throughout our lives. It’s recognizing, through emphasis or exaggeration, a fact about human life that is already true.

AW: When first reading through the collection, I expected technology to be a prominent element throughout every story. However, I noticed that electricity, in the literal and metaphorical sense, has drawn every story together instead. It was in pieces that lacked technology, like “The Woman Who Loved a Tree” and “Her Face I Cannot See,” that brought about a new dimension to electricity. There seemed to be a technical electricity, but also an emotional spark, or a spiritual spark. The sensation could be defined as electric. How do you see technology and electricity functioning within this collection?

EM: I haven’t thought about it this way before, but I think you’re right. Some of these stories are definitely about energy in general rather than just technological electricity, per se. In “The Woman Who Loved a Tree,” the protagonist falls in love with a tree in a park near her house. But what is really happening between them? The story can be interpreted as the woman imagining things, or it could be that she really has a connection with this nonhuman being. That feels like a way of thinking about electricity and energy to me. And in “Her Face I Cannot See,” the story becomes about the energy of psychological trauma that’s been stored inside the protagonist’s mind and heart and is only being released now. So yes, I love this expansion of the idea of electricity that you’ve articulated; that’s the current (so to speak) running through the stories.

AW: What I believe to be most poignant in the collection is the title piece, “The Church of Divine Electricity.” It describes this phenomenon where humans used to find the concept of “god,” outwardly. However, this story suggests a new era in which people are using technology and electricity to make their own “god,” or to worship “god.” How do you see this happening in the world around us? Is there any particular event that inspired this premise?

EM: When I wrote that story about five years ago, we weren’t yet in this burgeoning of generative AI that is occurring right now. But digital technology was already finding its way into more and more intimate aspects of our lives. The word you used — worship — is exactly the key. There’s a kind of reverence we sometimes have for technology, as though its trajectory is inevitable and can’t be questioned or altered. I’m not skeptical about using technology itself. That’s one of our species’ great gifts, the ability to imagine and model and create. But I think we need to step back from this idea that the process of its advancement is inevitably going to unfold in a certain way.

We’ve started to treat technological progress the way people have sometimes treated religion: as something too powerful to question, where the only correct response is awe and acceptance. What I feel strongly is that humanity maybe should, maybe must, ask whether this is necessary. Is it desirable? Who is controlling the technology we use and what goals do they have? What are the costs (environment, political, etc) to its widespread adoption? Are there other directions we might want to go, ways it could be made more fair, less harmful, more accountable? And we’re not having those conversations. Look at how AI companies have scraped writers’ books without consent — creative work that took years to make, stolen to train machines. Or the exploitation of workers, especially in the global south, by tech companies. The story comes from my unease about the speed and lack of accountability of these technologies.

AW: Something I really loved about the collection was that you use satire in such a darkly comical way. In the story “Life/Story,” you make a great commentary on the reader, as we are viewing an edited and curated, dramatized story of Martin’s life. In Mothers, the protagonist, a mother, loses her job because she is trying to improve her son’s disposition by giving him access to a “Mother” machine. In “The Woman Who Loved a Tree,” the protagonist’s relationship to the tree was described as the opposite of her new and unhappy marriage. As a reader, the seemingly “correct” action or answer is easy to identify, but in reality, we all fall short, and our lives can appear as satirical as the stories you present. How do you balance the gravity of content with the exaggeration of satire?

EM: There’s so much to make fun of in contemporary life, frankly. I try to turn the view so that the object of humor isn’t a real thing but something heightened, a slightly exaggerated version of what’s already in our culture. The use of satire and humor can be a way to get the reader close to something hard or painful. For example, in “Mothers,” the central technology is the enormous robot caregivers. The idea of adults being rocked to sleep by giant robots should strike us as strange. But it’s also absurdly close to what’s happening in real life, where people can’t get access to care (medical or therapeutic) that they need. There could be a realist story about inadequate healthcare and inequality, but humor allows us to get close to that reality in a way we can bear. Satire lets you laugh so that you can finally look.

AW: In the stories “Mothers,” “The Church of Divine Electricity,” and “The Woman Who Loved a Tree,” the story stops right before what would be classically defined as a climactic moment. How do you feel stopping short of a “big finale,” or resolution, influences how readers interpret the work?

EM: I love open endings in stories. Especially in short fiction, you can set the character on a trajectory, and as long as the reader knows where they’re headed, that’s enough. In “Mothers,” what matters is that the protagonist has decided to take this really significant risk at the end. She doesn’t know how it will turn out; it may not work, but that act of daring is the transformation. And in “The Woman Who Loved a Tree,” the story ends just before you find out what kind of world this is. Is she really in a relationship with that tree, or is she mistaken? You’re about to find out, and then it stops.

When I wrote that story, I’d been reading the critic Tzvetan Todorov, who calls that kind of story “the fantastic,” meaning a fiction where you’re not sure if there’s magic or not. That uncertainty is the point. I want the reader to reach the end and think, What do I believe? Do I want there to be magic, or do I not? Maybe you wish there was, or maybe you’re afraid there is. My aim is for the reader to push back on themselves a little, to think about their own expectations and desires. If that happens, then the story is working as intended.

Emily Mitchell is the author of a novel The Last Summer of the World, which was a finalist for the NYPL Young Lions Award, and two collections of short fiction, Viral and The Church of Divine Electricity, winner of the 2023 Elixir Press Fiction Prize. She has also published nonfiction in The New York Times, the New Statesman (UK), Guernica, and the Washington Independent Review of Books. She has published fiction in Prairie Schooner, The Sun, The Southern Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Missouri Review, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships from Yaddo, the Ucross Foundation, the Virginia Center for Creative Arts, and Can Serrat International Artists Residency. She serves as fiction editor for New England Review and teaches at the University of Maryland.

Alexia Woodall received her undergraduate degree in English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and is working toward a MA in English at UNL as well. Her specialization is in creative writing with an emphasis on creative nonfiction, fiction, and eating disorder studies. Her work has appeared in The Nebraska Poetry Society and UNL’s undergraduate literary journal Laurus.