December 10, 2014

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

1572 – Cornelis Musius, Dutch humanist/poet, is murdered at 72.

1821 – Nikolai A Nekrasov, Russian poet, writer and publisher (Russkije Zjenjshiny), is born.

1830 – Emily Dickinson, Amherst Mass, poet (Collected Poems), (d. 1886), is born.

1870 – Pierre Louijs, France, novelist/poet (Aphrodite, Woman & Puppet), is born.

1891 – leonie "Nelly" Sachs, German/Swedish poet (d. 1970), is born.

1931 – Max Elskamp, Belgian author/poet (Six Chansons), dies at 69.

1946 – Thomas Lux, American poet, is born.

A Little Tooth

Your baby grows a tooth, then two,

and four, and five, then she wants some meat

directly from the bone. It's all

over: she'll learn some words, she'll fall

in love with cretins, dolts, a sweet

talker on his way to jail. And you,

your wife, get old, flyblown, and rue

nothing. You did, you loved, your feet

are sore. It's dusk. Your daughter's tall.

—Thomas Lux

Your baby grows a tooth, then two,

and four, and five, then she wants some meat

directly from the bone.

—Thomas Lux

World Poetry

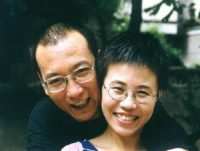

China: PEN Renews Calls for Release of Poet Liu Xiaobo and Wife Liu Xia

PEN is calling for immediate and unconditional release of Liu Xiaobo and wife, Liu Xia.

8 December 2014 marks the sixth anniversary of the arrest of Chinese poet and human rights defender Liu Xiaobo, who is serving an 11-year prison sentence for his dissident writings and peaceful activism. Liu Xiaobo was imprisoned for “inciting subversion of state power” for his part as the leading author behind “Charter ‘08”, a manifesto calling for protection of universal human rights and democratic reform in China.

PEN is calling for immediate and unconditional release of Liu Xiaobo and wife, Liu Xia

Recent Reviews

Poems About Poems

by Stephen Burt

If you write a book of poetry about sharks, you might get attention from readers who care about sharks. If you write a book of poetry that is explicitly and consistently about poetry—its institutions and conventions, how we decide what counts as poetry, what we expect it to do—you might get extra attention from readers who care about poetry, which is to say from anyone likely to pick up new poetry at all.

You and Me Both

by Dan Chiasson

The poet Olena Kalytiak Davis’s new book, her third, is “The Poem She Didn’t Write and Other Poems.” The title echoes, even as it undermines, an old formula that seems to have gone out of favor: Eliot’s “The Waste Land and Other Poems,” Yeats’s “The Green Helmet and Other Poems,” Ginsberg’s “Howl and Other Poems,” Plath’s “The Colossus and Other Poems” all come readily to mind, along with many slim but stately volumes before them. These titles conjure a world in which poetry was a game played across the ages, masterpiece versus masterpiece.

'The Best American Poetry 2014': Editor Terrance Hayes Makes A Brave Attempt to Identify the 'Best'

by Kristofer Collins

Any anthology that claims to be the “Best American” anything should give a reader pause. By what criteria does the editor judge and rank the sea of poems published in a given year? Is it even likely the editor has read every poem published in that year, and if not, then what are we to make of the classification “best” when all of the contenders for the title have not been given full consideration? Is “The Best American Poetry 2014” meant to be the last word in contemporary American poetics, or should we just relax and approach it as a casual ramble through the year that was? The more we parse the title, the deeper the quagmire presented by these collections.

The Glory Days

by William Logan

Louise Glück’s compelling, slightly creepy new book, Faithful and Virtuous Night, is stuffed with morbid fantasies, cracked allegories, offbeat fairy tales, and parables with no name.1 The speaker, who might be called Glück/not-Glück (if the world of these tales is unstable, so is character), reveals everything while revealing nothing—the poems are a raw look at identity constructed on the fly, which is, after all, not very distant from the way ordinary criminals live. If we trust Freud, we’re all ordinary criminals.

The title of Olena Kalytiak Davi’s new book echoes, even as it undermines, an old formula that seems to have gone out of favor.

Broadsides

Mark Strand’s Last Waltz

by Dan Chiasson

The passing of Mark Strand returns us to his poems and to his fine “Collected Poems,” published this year and long-listed for the National Book Award. Strand’s poems are often about the inner life’s methods of processing its social manifestations. He wrote poetry in quiet and private; on trains, he wrote prose, because it was “less embarrassing,” as he told his friend Wallace Shawn in Strand’s Paris Review interview: “Who would understand a man of my age writing poems on a train, if they looked over my shoulder? I would be perceived as an overly emotional person.” Strand was an “overly emotional person,” but his courtesy warred with his intensity. How gallant to think of the passenger beside him, whose rights extend to not being seated next to a handsome stranger scribbling verses.

Disability and Poetry

An Exchange

by John Lee Clark and Jennifer Bartlett and Jillian Weise and Jim Ferris

Jennifer Bartlett: I have resisted the term “identity poet” when considering my own work; therefore, my biggest challenge is to address my cerebral palsy without poetics and other identities taking a “back seat” in the process. Ableism in the work of others doesn’t consciously affect how I write my poems. Poems for me are not a conscious endeavor. In the tradition of Jack Spicer, I just listen to the “Martians” and write down what they tell me.

The Social Conscience of Elizabeth Bishop

by Michael Young

When I first read Bishop as a young poet, I was dazzled by her perfect syntax and rhythmic modulation, the nearly flawless detail of images. Rereading her as, I would like to think, a mature poet, I am struck by the power of her social conscience. Pity is the underlying feeling she conveys, compassion and a deep feeling for the injustice of privilege.

Pity is the underlying feeling Elizabeth Bishop conveys, compassion and a deep feeling for the injustice of privilege.

Drafts & Fragments

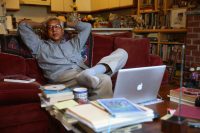

Vijay Seshadri Struggles With Watching Football

by Liz Robbins

Vijay Seshadri was born in Bangalore, India, and first earned recognition when his poem “The Disappearances” graced the back page of The New Yorker after September 11. Since he won the Pulitzer Prize in April for his poetry collection “3 Sections,” he has frequently traveled to lectures on weekends. During the week, he teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. His fall Sundays used to include a guilty pleasure: watching football. But like many other N.F.L. fans, he is struggling to reconcile the violence related to the game with his love for it, describing the pastime as a result of a “fatal moral compromise.” Mr. Seshadri, 60, has lived in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, since 1986 with his wife, Suzanne Khuri, 58. Their son, Nicholas, 22, now lives in Manhattan.

COROLLAIRE À L’IDENTIFICATION DU «COUP DE DÉS» D’APRÈS LES CLASSIFICATIONS D’HENRI POINCARE

by Jean-François Bor

Jean-François Bory (1939, Paris, France) – poet, essay writer, photo-artist, publisher. He is the author of more than thirty books of poetry, prose and artist’s albums. He was the co-editor of the magazine “Approches” (4 issues, 1965-69, in collab. with J. Blaine), in the early 1970s he initiated publishing of the historically and experimentally oriented periodical magazine “L’Humidite” (25 issues, 1970-78).

But like many other N.F.L. fans, Vijay Seshadri is struggling to reconcile the violence related to the game with his love for it.

Poetry In the News

UNL Professor Finds 'New' Poem by Walt Whitman

Wendy Katz was working as a Smithsonian senior fellow in Washington, D.C., researching art criticism in the penny newspapers, when she found a poem in the June 23, 1842 issue of the "New Era" by "W.W."

Claudia Emerson, Award-winning Poet and Professor, Dies at 57 after Battle with Cancer

Claudia Emerson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, died early Thursday morning at age 57 after a long battle with cancer, the university said. Emerson, a native of Chatham, Virginia, won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her book "Late Wife," a collection of handwritten letters reflecting on her failed marriage of 19 years and her blossoming relationship with her second husband, Kent Ippolito. For three years, Emerson took the letters — never mailed — and taped them to the walls of her home and office. In an interview with The Associated Press after she won the prize, Emerson said she drew on the complex emotions of two people trying to rekindle a love they once believed was gone from the world.

In His New Musical, Renowned Poet Gary Soto ‘Dreams a Dream’

Never suggest that Gary Soto, the nationally renowned poet and author who was born and raised in Fresno, doesn’t like to try new things. When he was commissioned to write a play for a San Francisco youth theater on the timely topic of the Dreamers, the large group of undocumented students who have been raised and schooled in the U.S., Soto said no way. “It can’t be a play,” he said. “It needs to be a musical. It needs to be life-filled and loud.”

Claudia Emerson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, died early Thursday morning at age 57.

New Books

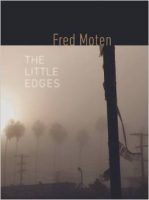

The Little Edges by Fred Moten

[Hardcover] Wesleyan, 72 pp., $22.95

The Little Edges is a collection of poems that extends poet Fred Moten’s experiments in what he calls “shaped prose”—a way of arranging prose in rhythmic blocks, or sometimes shards, in the interest of audio-visual patterning. Shaped prose is a form that works the “little edges” of lyric and discourse, and radiates out into the space between them. As occasional pieces, many of the poems in the book are the result of a request or commission to comment upon a work of art, or to memorialize a particular moment or person. In Moten’s poems, the matter and energy of a singular event or person are transformed by their entrance into the social space that they, in turn, transform. An online reader’s companion is available athttp://fredmoten.site.

The Poem She Didn't Write and Other Poems by Olena Kalytiak Davis

[Hardcover] Copper Canyon Press, 110 pp., $23.00

“Davis’ first full collection in a decade should be stamped with the warning, ‘Buckle up!,’ because entering this writer’s mind is one wild ride of digression, mutation, and syntactical and typographical experimentation… Davis has clearly put the poetic rule book through a shredder, and there’s much to appreciate about that.”—Booklist

Chamber Music: The Poetry of Jan Zwicky edited by Darren Bifford and Warren Heiti

[Paperback] Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 102 pp., $16.99

Arcing across thirty years and seven volumes, Jan Zwicky’s poetry has always been acutely musical (and sensitive to the silence out of which music comes). In the compositions in Chamber Music, the first anthology of Zwicky’s poems, one may perceive the attunement of her vocations: poet, philosopher, violinist. Her poetry both praises and relinquishes the earth, bearing witness to the fierce skies of the prairies and the freezing rain of the West Coast. Enacting the virtue of clarity prized and defended by her explicitly philosophical work, this poetry is both resonant and integrated. It is also formally diverse, ranging from the singular focus of the lyric ode to suites of variations and fugal structures, from polyphonic textures to the sprawling reach of narrative gestures.

The Little Edges is a collection of poems that extends poet Fred Moten’s experiments in what he calls “shaped prose.”

Correspondences

To Be Moved by a Poem

stephen e. leckie in Conversation with Anne Compton

Malahat volunteer stephen e. leckie talks with poet Anne Compton about her contribution of three poems to Issue 187, our upcoming Summer 2014 issue. Compton is the winner of numerous literary awards, including the Atlantic Poetry Prize, the Governor General's Award for Poetry, and a National Magazine Award in Poetry. Read on to learn about Compton's take on language, process, and inspiration.

The Dilemma of Two Masters: An Interview with Adele Kenny

by Micah Towery

NOTE: Adele and I started this interview a while back and I never had the chance to post it. Some of the elements refer to her book What Matters as a recent publication.

MT: I first want to comment on what I see as the arc of this collection, What Matters. Memory, in this book, seems like a kind of sacrament: memorializing literally makes real by nature of the act. I’m thinking especially of the line “language…larger than / logic” (“The Sap Bush”). (I’ve chopped that line up, but it seemed so evocative to me that I couldn’t bypass it.) The first section fulfills and meditates on this traditional task of the poet. Then the second section puts that function into crisis—the poet dies (or rather confronts the possibility of her own death). The crisis is (I think), if the memorializer dies, how do those that the poet loves (including herself) continue to exist? This crisis gives birth to the third section, which affirms “We Don’t Forget,” but is admittedly much more subdued (chastened?) in its memorializing.

The Golden Mean: Dorothea Lasky and the Well-Adjusted Poem

by Felix Bernstein

Dorothea Lasky is the Ello of poetry. She gives us poems that are cute and zany, but on a clean, ad-free platform that is friendly, complex, and interpersonally sensitive. She is poetry’s golden mean between radical and legible, romantic and classical, interpersonal and impersonal: in other words, she is uniquely poised to transcend the poetry wars. In this way, she is an heir to the throne that W.H. Auden left to John Ashbery, who is a central figure in her life, and has famously been accepted by the avant-garde and the mainstream; the queer and the heteronormative.

stephen e. leckie talks with poet Anne Compton about her contribution of three poems to Issue 187.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Misunderstanding Poetry

by Joseph Spece

I took the AP Literature examination near the end of my junior year in high school. From what I recall, the test was straightforward—little impacted me save for Richard Wilbur’s poem “The Death of a Toad.” And ‘impact’—originating from the Latin impingere, ‘drive something in or at,’ ‘thrust at forcibly’—was precisely the word: our proctor, another English teacher, actually noted my hovering over the page as time ticked away (I suppose she thought it an inordinate amount of time) and asked if I was feeling alright.

——————————

In his reading of the Wilbur poem, the author quarrels with the AP exam answer regarding the tone of the poem. He claimed that the tone was earnest whereas the correct response according to the examiners was that it was ironic or morbidly comic.

In a letter to a high school English teacher about the poem, Wilbur remarks on the tone:

"The first two lines of the third stanza are out to associate to toad with those "primal energies" — and of course there is biological ground for doing so. The words are out to magnify the toad and at the same time to be disarming about that — to acknowledge by an undertone of humor that I am making a great deal of a very small creature. My tonal ambiguity has worked for some readers but did not work, as I recall, for Randall Jarrell."

The "undertone of humor" is not exactly morbid comedy. It is self-awareness, distancing, to acknowledge that there is an inflation here that might be out of proportion, but it doesn't need therefore to reflect a lack of earnestness. I think the author is justified in his interpretation of the poem's tone. Wilbur himself calls it "tonal ambiguity."

It's really only those two lines:

Toward misted and ebullient seas

And cooling shores, toward lost Amphibia’s emperies.

that belie the over-the-topness of Wilbur's rhetoric. I would argue that those alone aren't enough to negate the earnestness of the poem's meaning as Joseph Spece has interpreted it.

For a little more tonal clarity on a similar subject, look at Larkin's poem, "The Mower" which covers some of the same ground (so to speak):

The Mower

The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found

A hedgehog jammed up against the blades,

Killed. It had been in the long grass.

I had seen it before, and even fed it, once.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be careful

Of each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same

–The Mower