July 24, 2012

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

July 24, 2012

1738 – Elizabeth “Betje” Wolff-Bekker, Dutch author/poet (Sara Burgerhart), is born.

1758 – John Dyer, poet, dies.

1862 – Johan A de Sleeve, [Adwaita], philosopher/classical/poet (Brahman), is born.

1867 – Vicente Acosta, Salvadoran poet (d. the same day 1908), is born.

1908 – Vicente Acosta, Salvadoran poet (b. the same day 1867), dies.

2000 – Ahmad Shamlou, Iranian poet (b. 1925), dies.

The lovers

The lovers

passed by, heads hanging lowly,

ashamed of their untimely songs.

And since then,

the lanes remained void and silent.

The soldiers

passed by, broken and drown,

riding their ghostly horses, and

with the fading stains of their hubris

all over their blades.

from “Closing Game” by Ahmad Shamlou (1925–2000)

Poetry In The News

Poetry Aficionados Disappointed and Naked at the Bowery Poetry Club Farewell

Angry Bob gets angry. On it’s final night of operation (at least as the unique and wonderfully dingy place it has been for the past ten years) the Bowery Poetry Club on Bowery and 1st Street, a long-time haven for the starving artists of lower Manhattan, expressed its perfect weirdness in more ways than one. Read more at Velvet Roper.

Angry Bob gets angry. On it’s final night of operation (at least as the unique and wonderfully dingy place it has been for the past ten years) the Bowery Poetry Club on Bowery and 1st Street, a long-time haven for the starving artists of lower Manhattan, expressed its perfect weirdness in more ways than one. Read more at Velvet Roper.

Party Honors Hemingway as Poet

Never knew that Ernest Hemingway tried his hand at poetry? Don’t feel bad. Hemingway apparently didn’t think much himself of the 50 or so poems he wrote during his life, mainly for family and friends and only a handful were published. In a sense, though, the Nobel Prize-winning author remained a poet throughout his career, according to Poetry Foundation president John Barr, who will speak on “Hemingway’s Poetry in Prose” during a celebration of his birthday July 21 at the Hemingway Museum in Oak Park. Red more at the Sun-Times.

World Poetry

Cuban Erotic Poetry Turns 90

Insolent, angry, wicked that’s me/Or so you say before you angrily look away/Faith is so yesterday/Tomorrow is where I want to be.

Poet, painter, journalist, filmmaker and television personality Pritish Nandy has used the 140-character format to transport poetry to the age of Twitter in a new anthology, “Stuck on 1/Forty”. But he says his 140-character poetry does not mark a new phase in the evolution of the popular literary genre, it is just another form of creative expression. Read more at the New York Daily News.

New Books

Dickinson Unbound: Paper, Process, Poetics by Alexandra Socarides

[Hardcover] Oxford University Press, 224 pp., $49.95

[Hardcover] Oxford University Press, 224 pp., $49.95

Dickinson Unbound gives us a Dickinson at once more accessible and more complex than previously imagined. As the first authoritative study of Dickinson’s material and compositional methods, this book not only transforms our ways of reading Dickinson, but advocates for a critical methodology that insists on the study of manuscripts, composition, and material culture for poetry of the nineteenth century and thereafter.

World’s Two Smallest Humans by Julia Copus

[Paperback] Faber & Faber, 64 pp. (no price listed)

Julia Copus’ poems bring humanity and light to some of our most intimate and solitary moments, repeatedly breathing life into loss. In two previous collections, she has been feted as among the most compelling poets to have emerged in recent years; now, in The World’s Two Smallest Humans, she is writing at her most captivating yet. These finely tuned poems are the fruit of her upbringing in a musical family, an affinity with the Classics, a fascination with the arc of time, and an unflinching scrutiny of love and personal relationships.

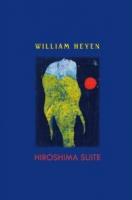

Hiroshima Suite by William Heyen

[Hardcover] Nine Point Publishing, 88 pp., $19.95

[Hardcover] Nine Point Publishing, 88 pp., $19.95

I invite you to allow this remarkable Hiroshima Suite which he seems to have heard all at once in one non-linear audition to intone for you until, within the transluminous horror of August 6, 1945, we are never not whole again but are, at the same time, in Robert Frost’s phrase, “beyond confusion.”

The View We’re Granted by Peter Filkins

[Paperback] The Johns Hopkins University Press, 80 pp., $19.95

In the pivotal poem “Marking Time,” which appears almost exactly halfway through Peter Filkins’s fourth collection of poetry, the speaker reflects on the death of a sibling and how time is marked by our memories. These memories, these moments—whether spent contemplating a painting by Vermeer or the simple toss of a bean bag—ultimately shape who we are. “Yet you are with me here, with me here again, / where neither that moon nor you exist, but live / tethered to this memory composed of words.”

Recent Reviews

The Resurrecting Inspiration of Jehanne Dubrow’s Stateside

by Diana Hartman

As a Marine spouse I get a lot out of hearing the different impressions other military spouses have of the same events we all endure. For me, though, it is an odd hate/love relationship I have with the writings of other military spouses when the subject gets personal and painful. I can barely re-read my own pain, much less get through someone else’s perspective of it. I wonder if it’s because I’m also a writer. We often write what we cannot or will not say. For the military spouse, a lot of what goes unspoken could burn a hole through paper and its fire can only be put out by exasperated tears of anxious frustration. Read more at Blog Critics.

New Translation of the Bhagavad Gita!

by Ann Kjellberg

A new translation of the Bhagavad Gita from Norton by Gavin Flood and Charles Martin sent me into Namaste on 14th Street for a comparison. Flood and Martin’s introduction is welcoming and informative; I took note especially of their description of the poem’s form, which echoes the larger epic, the Mahabharata, in which it sits. The news is that Sanskrit epic poetry is, like Latin and Greek, quantitative, arranging patterns according to length of syllable, a quality we no longer hear. Read more at Little Star.

The Contortions of T. S. Eliot’s Christianity

by Adam Kirsch

So far, each volume of the letters of T. S. Eliot has stood under the sign of one of the poet’s major works. The first volume, which went up to the year 1922, showed us the young Eliot desperately trying to escape the fate of Prufrock, the ineffectual, well-bred man. His hasty 1915 marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood and his consequent decision to remain in England instead of returning to a professorial career in the United States can only be understood as a death blow dealt to the poet’s inner J. Alfred. Read more at the New Statesman.

Dear Life by Dennis O’Driscoll

by Fran Brearton

Dennis O’Driscoll has never been, as he himself says, “party to income tax work”; but his long career in the office of Ireland’s Revenue Commissioners, moving from death duties to stamp duty, puts him, like Stevens or Larkin, in the tradition of “office poets” whose writing lives may be practically circumscribed by their civil (or other) service – the “toad work” as Larkin had it – but whose vocabularies and perspectives on “life” are unusually and productively enriched thereby. Read more at the Guardian.

Correspondences

“How Did Poetry Survive?”

y Serena Golden

Poetry, John Timberman Newcomb believes, has lost status in recent years. In the introduction to his new book, How Did Poetry Survive? The Making of Modern American Verse (University of Illinois Press), Newcomb argues that American poetry has been “segregat[ed] … from modern social experience” — with the result that poetry is hardly even considered “literature” anymore. This isn’t the first time that American poetry’s star has waned. In How Did Poetry Survive?, Newcomb traces the genre’s changing fortunes at the turn of the 20th century, arguing that poets’ engagement with modern topics and “ordinary life” played a key role in their works’ return to widely acknowledged cultural relevance. Read more at Inside Higher Ed.

Broadsides

Ghosts in the City

by Hilary Chung

At the time of the events of June 4th 1989 in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square two controversial Chinese poets, Yang Lian and Gu Cheng, found themselves in Auckland, New Zealand. While both had taken advantage of a relaxation of the political environment in China during the latter half of the 1980s to travel abroad, their subsequent lives came to be defined by these events as political exile. Both poets remained based in Auckland until 1993 but the circumstances of their exile, their relationship to their place of exile and its expression in their poetry are in marked contrast to one another. This paper explores this contrast through a close reading of two landmark poems in which both poets use the motif of the ghost to evoke their exilic state. Read more at ka mate ka ora.

Obama’s Oddest Critic

by Eric McHenry

In the spring of 1981, a seemingly unremarkable poem called “Pop” appeared in the Occidental College literary magazine. It began: Sitting in his seat, a seat broad and broken/

In, sprinkled with ashes

/ Pop switches channels, takes another

/ Shot of Seagrams, neat, and asks

/ What to do with me, a green young man

/ Who fails to consider the/

Flim and Flam of the world… On the surface, it is a poem about a young man’s relationship with, and ambivalence toward, a paternal figure. But in recent years, attentive readers have noticed some extraordinary subtext: In fact, it is a poem about pederasty and sexual abuse. Read more at Salon.

Drafts & Fragments

Missed Connections Poetry on Craigslist

by Alan Feuer

It’s certainly the case that sexual attraction generates heat. But what about the converse? Can heat — actual, nonmetaphorical, summer city heat — inspire lustful feelings? It would seem so, according to these poems “found” last week in the Missed Connections section of newyork.craigslist.org. They are printed verbatim, with only line and stanza breaks added; their titles are the subject headings. Read more at the New York Times.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Impossible to Tell: On Robert Pinsky

Jeremy Bass

Jeremy Bass

Is there a poet more visible in contemporary American culture than Robert Pinsky? In addition to receiving many well-deserved awards, Pinsky has placed himself before the camera’s eye more often than most writers, let alone poets, appearing on both The Colbert Report and—as himself—in an episode of The Simpsons. His role as unofficial ambassador of poetry is not without justification: the only US poet laureate appointed to three consecutive terms (1997–2000), Pinsky dedicated much of his initial time in the post to establishing the Favorite Poem Project, a multimedia venture that invites Americans of all cultural persuasions to read, record and discuss their favorite poems. Read more at The Nation.

I suppose we all have quarrels with the famous in our fields. I have mine with Robert Pinsky. He sometimes comes off, well-meaning and earnest though he may be, like an evangelist for poetry—even when the room he is speaking to is filled up to its amphibrach with poets who need no further conversion. His nationwide campaign strikes me as similar to that of John Ciardi who blanketed the country by radio, television, and public lecture in the early sixties announcing the gospel of poetry to the stressed and unstressed like. Whereas Pinsky has The Colbert Report, Ciardi had The Tonight Show. That being said, the discussion in this article of Pinsky’s relationship with the lessons of his teacher Yvor Winters reflects, if true, something of a redemption for Pinsky, at least in my eyes. The article says:

“Pinsky would take two important lessons from his time at Stanford with Winters: an unfashionable belief that ‘prose virtues…. Clarity, Flexibility, Efficiency, Cohesiveness’ are essential to a poet’s technical repertoire; and an openness to the available traditions of poetry, to work by poets other than his like-minded contemporaries, no matter where they fell on the stylistic or political spectrum.”

Winters’ lessons for Pinsky and for all his students*, including those of us who never knew him, are rendered succinctly both in word and in example in the following poem, particularly the final stanza. —David Sanders

*Other Winters students and protégés include Thom Gunn, Donald Hall, J. V. Cunningham, Turner Cassity, Kenneth Fields, N. Scott Momaday, Robert Hass, John Peck, Philip Levine, Edgar Bowers, Donald Justice, and Helen Pinkerton.

To a Young Writer

Achilles Holt, Stanford, 1930

Here for a few short years

Strengthen affections; meet,

Later, the dull arrears

Of age, and be discreet.

The angry blood burns low.

Some friend of lesser mind

Discerns you not; but so

Your solitude’s defined.

Write little; do it well.

Your knowledge will be such,

At last, as to dispel

What moves you overmuch.

—Yvor Winters