March 23, 2017

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

1639—Thomas Carew, English poet/diplomat (The Rapture), dies.

1857—Arnold Sauwen, Flemish poet (Along the Meuse), is born.

1905—Phyllis McGinley, poet, is born.

1941—Billy Collins, American poet, is born.

I want them to waterski

across the surface of a poem

waving at the author’s name on the shore.

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

—from “Introduction to Poetry” by Billy Collins

“I want them to waterski / across the surface of a poem” – Billy Collins

World Poetry

Derek Walcott, Poet and Nobel Laureate of the Caribbean, Dies at 87

Derek Walcott, whose intricately metaphorical poetry captured the physical beauty of the Caribbean, the harsh legacy of colonialism and the complexities of living and writing in two cultural worlds, bringing him a Nobel Prize in Literature, died early Friday morning at his home near Gros Islet in St. Lucia. He was 87. His death was confirmed by his publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. No cause was given, but he had been in poor health for some time, the publisher said.

The Newly Discovered Post-WWII Purim Poem that Comforted Survivors

His fellow patients needed a good laugh, so Yisroel Meir Schwartz put pen to paper and began writing — first in black ink, then blue. It was 1947 and Schwartz, who had survived several years in a traveling forced labor detail, was recovering from tuberculosis in a displaced persons (DP) hospital in Gauting, a suburb of Munich. Now Purim was coming and it was time for some levity. The situation called for some traditional Purim grammen, or verse — performed in a call-and-response singsong shared between reader and audience.

Derek Walcott died early Friday morning at his home near Gros Islet in St. Lucia. He was 87.

Recent Reviews

Beautiful Poems About a House of Horrors

by Dwight Garner

Molly McCully Brown’s first book of poems, “The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded,” is part history lesson, part séance, part ode to dread. It arrives as if clutching a spray of dead flowers. It is beautiful and devastating. The title refers to an actual place. The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded was a government-run residential hospital in Amherst County, Va. It opened in 1910.

Southern Sublime

by Julian Lucas

The solitary artist on the snowy ridge of Peter Doig’s Figure in Mountain Landscape (1997–1998) couldn’t be farther from the Caribbean. Back turned, he looks over his easel toward a smattering of evergreens on a mauve hillside. It is winter, but there is hardly any white on the canvas, and the distant lime-green mountains suggest the arrival of spring. The painter, a flame in the wilderness, seems almost to smolder, covered in jagged pink patches as though pictured by a thermographic camera. Derek Walcott’s poem on the facing page begins with serene indifference to climate or continent, describing the painter as the poet’s houseguest. A studio is mentioned; shortly thereafter, a pool. Discrepancies accumulate and we begin to wonder where, between text and image, we have disembarked. But the poem’s final lines excuse this sleight of land, invoking the painter’s peripatetic biography and the deceptive license of his art.

On Monica Youn’s Blackacre

by Tess Taylor

As well as being one of the most consistently innovative poets working today, Monica Youn is a Yale-trained lawyer. And so as all lawyers do, she learned in property law that blackacre is a centuries-old legal term that stands in for a fictitious estate. In legal practice, positing a blackacre has been used to explore laws about easements or environmental rights or whether or not farmer A will eventually owe farmer B potatoes. This might be a bit far afield from poetry, but in this case, the estate Youn is looking to claim is the estate of the body, specifically the body that wants to conceive a child.

Time’s Technique: On Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s “No Way Out But Through”

by Rachel Hadas

Lynne Sharon Schwartz is a novelist and memoirist and translator, a writer of excellent prose. And galling as it may be for a poet like me, possessed of no narrative talent, to acknowledge, Schwartz is also a poet of poise and power. No Way Out But Through, Schwartz’s third collection of poems, showcases some of this writer’s many strengths. She’s a stubborn anti-sentimentalist who can write wrenching elegies. She’s an archivist of memories, a celebrant for the forgotten or nearly forgotten, who also writes eloquently of the undertow of oblivion. She’s an anthologist of anxiety dreams. Irritated by Cordelia and partial to the Fisherman’s Wife, she’s a contrarian reader. At all times, Schwartz’s poetic voice is piercingly honest. Her tough-minded intelligence leaves plenty of room for questions and regrets.

Molly McCully Brown’s book, “The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded,” is part history lesson, part séance.

Broadsides

The Golden Ratio: Poetry & Mathematics

by Emily Grosholz

In his book The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard talks about the house of childhood, the house we never leave because at first we live in it, and afterwards it lives on in us. The house of childhood organises our experience, first of all determining inside and outside, and then offering middle terms: the front porch and its steps are a middle term between the house and the town, while the back yard and garden are a middle term between the house and the wild. (In the proportion between two ratios expressed in A:B :: B:C (or ‘A is to B as B is to C’, we call B the middle term, which brings A and C into clear relation.) It organises what is far away, because we measure ‘away’ by how far it is from home, how many hours or days of travel. Moreover, the windows of the house let in the distances, the dwindling train tracks, river or road, the fields and forest, even the cloudy-blue or starry heavens: they are set squarely on the walls within the window frames, as light comes through and we see what is outside. It also organises time.What lives in the basement or the attic? We ourselves do not eat or sleep or socialise or read there, though those rooms are part of the house: they are where we put the past, the discarded and the treasured. Finally, the house invites playing: the playroom with its gate and the fenced part of the backyard, enclosures where the toys are kept and children imitate the human activities of building and furnishing houses, admonishing and encouraging their dolls, rushing about on small basketball courts and soccer pitches, setting forth amidst the ceremonies of departure and return.

Where We Go From Here: On “Political” Poetry and Marginalization

by Cynthia Cruz

“But one voice is not enough, nor two, although this is where dialogue begins.” — Cherrie Moraga

The Problem

Something occurred during the days after the Trump election. There was a marked difference between those who were angry and shocked and those who experienced the news of Trump’s election as just one more event in a lifelong series of such events. For the former group, who tended to be white middle class women and Clinton supporters, Trump’s election was a call-up. Many had not previously been political. They had seen themselves reflected in Hillary Clinton. They identified with her.

In his book “The Poetics of Space,” Gaston Bachelard talks about the house of childhood.

Drafts & Fragments

Trump Wrongly Cited Lines from a Nigerian Poem as an Irish Proverb for St. Patrick’s Day

by Yomi Kazeem

The world has learned to take things US president Donald Trump says with a pinch of salt and in celebration of a day more synonymous with pints of beers and shamrocks, president Trump delivered another one of his odd gaffes. In a St. Patrick’s Day reception with Enda Kenny, the Irish prime minister, Trump quoted words from what he appeared to believe was an Irish proverb.

On St. Patrick’s Day, Trump wrongly said lines from a Nigerian poem were from an Irish proverb.

Poetry In the News

Kevin Young Is Named Poetry Editor at The New Yorker

Paul Muldoon, who for a decade has served as the poetry editor of The New Yorker, will step down, the magazine announced on Wednesday. His successor will be Kevin Young, who moved to New York from Atlanta last year to become the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Mr. Young is an esteemed poet and scholar whose work has been published in The New Yorker dating back to 1999.

Trump Proposes Eliminating the Arts and Humanities Endowments

A deep fear came to pass for many artists, museums, and cultural organizations nationwide early Thursday morning when President Trump, in his first federal budget plan, proposed eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. President Trump also proposed scrapping the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a key revenue source for PBS and National Public Radio stations, as well as the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Paul Muldoon, who for a decade has served as the poetry editor of The New Yorker, will step down. His successor will be Kevin Young.

New Books

Field Theories by Samiya Bashir

[Paperback] Nightboat, 72 pp., $15.95

These poems span lyric, narrative, dramatic, and multi-media experience, engaging their containers while pushing against their constraints. Field Theories wends its way through quantum mechanics, chicken wings and Newports, love and a shoulder's chill, melding blackbody theory (idealized perfect absorption, as opposed to the whitebody's idealized reflection) with real live Black bodies. Albert Murray said, "the second law of thermodynamics ain't nothing but the blues." So what is the blue of how we treat each other, ourselves, of what this world does to us, of what we do to this shared world? Woven through experimental lyrics is a heroic crown of sonnets that wonders about love and intent, identity and hybridity, and how we embody these interstices and for what reasons and to what ends.

Rock|Salt|Stone by Rosamond King

[Paperback] Nightboat, 72 pp., $15.93

Rock|Salt|Stone sprays life-preserving salt through the hard realities of rocks, stones, and rockstones used as anchors, game pieces, or weapons. The manuscript travels through Africa, the Caribbean, and the USA, including cultures and varieties of English from all of those places. The poems center the experience of the outsider, whether she is an immigrant, a woman, or queer. Sometimes direct, sometimes abstract, these poems engage different structures, forms, and experiences while addressing the sharp realities of family, sexuality, and immigration.

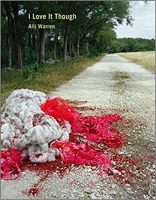

I Love It Though by Alli Warren

[Paperback] Nightboat, 72 pp., $15.95

Alli Warren’s I Love It Though looks hard at the material and affective world we’ve inherited, including the ordinariness of the sublime and the sublimity and transcendence of what’s most ordinary. This book makes meaning of our contemporary moment, both sharp and vulnerable, concrete and musical. These poems are committed to living in the present, delirious with outrage and hope for something better.

Here High Note, High Note by Catherine Blauvelt

[Paperback] Prelude Books, 80 pp., $15.00

"Full of vatic intrigue and exuberance, Catherine Blauvelt's poems demonstrate again and again how lexical intoxication can lead to clarity and wisdom, and, vitally, that a poem is a site of celebration no matter its tragic sources and discoveries. Here is a book for what ails us." —Dean Young

Transom by Rick Mullin

[Paperback] Dos Madres Press, 82 pp., $18.00

Rick Mullin’s Transom is a poet s Odyssey through the year 2016 set primarily in the financial district of Manhattan. The poems are written in a 15-line sonnet variant of Mullin's device, a form called the Third Sancerre. With views of the city from the docks at Hoboken s Lackawanna Terminal, from the top deck of the Ferry Stevens, and from the city s oldest streets there are a few excursions to such places as Lake Charles, LA; Ithaca, NY; Cape May, NJ; and Cologne, Germany Transom logs the portents, "public and personal" of a transitional

Alli Warren’s “I Love It Though” looks hard at the material and affective world we’ve inherited.

Correspondences

Interview with NBCC Poetry Winner Ishion Hutchinson

By Matthew L. Thompson

Thanks to the cooperation of the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) and Creative Writing at The New School, as well as the tireless efforts of our students and faculty, we are able to provide interviews with each of the NBCC Awards Finalists for the publishing year 2016.

Across the Slippery Tabletop: An Interview with Keetje Kuipers

by Cate Lycurgus

Keetje Kuipers has been a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, the Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College, and a Bread Loaf Fellow. A recipient of the Pushcart Prize, her poems have appeared in such publications as American Poetry Review, Orion, West Branch, and Prairie Schooner. In 2007 Keetje completed her tenure as the Margery Davis Boyden Wilderness Writing Resident, which provided her with seven months of solitude in Oregon’s Rogue River Valley. She used her time there to complete work on her first book, Beautiful in the Mouth, which was awarded the 2009 A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize and was published by BOA Editions. Her second book, The Keys to the Jail, was published by BOA Editions in 2014. In 2016, Keetje left her position as a tenured Associate Professor at Auburn University, where she was editor of Southern Humanities Review, to write full-time. She lives with her family in Seattle.

Keetje Kuipers has been a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and a Bread Loaf Fellow.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Derek Walcott

The death of Derek Walcott marks a significant passing. He was a giant of a poet, of which there are only a few left roaming the planet. Let's consider some of Walcott's words on the state of American poetry,on his appraisal of our understanding of our poetry, and on his idea on rhyme, taken from an interview with Rose Styron published in the May/June 1997 edition of American Poetry Review.*

"American arrogance can be astounding. American arrogance about esthetics […] Saying we have gone beyond rhyme and we have gone beyond X or Y — I have had too many maimed students, I think, crippled students, who have come to me from certain classes from somewhere, in which they have been told not to use rhyme, there is too much melody. Someone said to me: once I was told, try to avoid music. This is the only culture in the history of the world that has ever said that about verse. Absolutely. This is ridiculous — it’s absurd. The apocalypse."

"Dickinson is the greatest American poet. Okay? She is wider and deeper than Whitman. She is more terrifying than Whitman. There is no terror in Whitman. […] When you learn finally to come to Dickinson and realize that here in a box-shape — you know, very tight stanzas, that are like little prisms of things — all this experience is contained, and that the half-lines are staggering, astonishing, frightening — that that little box contains more in it than the loud, amplified line of Whitman, then you are a mature person. Then you have grown up."

"I think one of the reasons why I use rhyme, is because rhyme takes over, right? There’s one kind of reason […] which I think is a prosaic reason, which says, this is the subject, and stick to it—you know? And this is the prose reason.Whereas if you use a rhyme—let’s say you’re heading toward the end of a line, then you find a rhyme—whatever the design of it—it could be far down, but I think all poems are based on the concept of rhyme. Every poem is based on that idea. It’s used or it’s not used, but the instinct is that. So if you are using rhyme, when it does happen, when you’re heading towards those last couple of syllables, and you’re desperate, and you don’t know what it’s going to be, and if it does happen, then it can alter meaning. It can absolutely lift meaning in a certain direction or in another direction, and what you then do is you have to follow what the subterranean thing that has suddenly emerged dominates in your direction.And you keep following that, and you’re still trying to maintain direction, some original direction, but you’re discovering what you’re writing, as you write it, you know? And that’s when it becomes magical. But that’s not common.That’s not often."

* with thanks to Geoff Brock for bringing them to my attention.

The death of Derek Walcott marks a significant passing. He was a giant of a poet.