May 15, 2012

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

May 15, 2012

1865 – Albert Verwey, Dutch poet/literature historian (Motion), is born.

1886 – Emily Dickinson, US poet, dies at 55.

1920 – Hugh Henry Home Popham, aviator/writer/poet, is born.

1924 – Jaime Garcia Terre (died 1996), poet/essayist, is born.

1993 – Salah Ahmed Ibrahim, Sudanese writer, poet, and diplomat (b. 1933), dies.

The show is not the show,

The show is not the show,

But they that go.

Menagerie to me

My neighbor be.

Fair play—

Both went to see.

—Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

Poetry In The News

A Poet Taps the Power of His Art

Harry Staley, stooped and gaunt, gripped a metal walker and shuffled to a podium to read his poetry in the Writers Institute offices at the University at Albany. The audience of about 40, friends and former students, held its collective breath. Staley, 87, struggles with dementia. The professor emeritus of English, a legendary teacher to two generations of University of Albany students, has become a mostly vacant, pleasantly pliant version of his intellectually fierce and disarmingly witty former self.

Read more at the Chicago Tribune.

World Poetry

Another Attack On Pakistan’s Dead Poets

Forget the youthful bloggers, pro-democracy crusaders and TV celebrities who launched Russia’s five-month-old movement of street protests against autocratic rule. The anti-Kremlin crowd has a new unifying symbol: Abai Kunanbayev. Never mind that he lived 2,000 miles away on the Central Asian steppe and died nearly 108 years ago. Or that few Russians had heard of him until this week. The Kazakh poet, composer and philosopher—represented by a 20-foot-tall bronze statue—just happened to be in the right place at the right time. Read more at the Wall Street Journal.

Forget the youthful bloggers, pro-democracy crusaders and TV celebrities who launched Russia’s five-month-old movement of street protests against autocratic rule. The anti-Kremlin crowd has a new unifying symbol: Abai Kunanbayev. Never mind that he lived 2,000 miles away on the Central Asian steppe and died nearly 108 years ago. Or that few Russians had heard of him until this week. The Kazakh poet, composer and philosopher—represented by a 20-foot-tall bronze statue—just happened to be in the right place at the right time. Read more at the Wall Street Journal.

Persian Poetry Power: Writers are Bringing the Spirit of Iran’s Verse to Britain

Three years ago, in a garden full of cypress trees, I watched men and women kissing a marble tomb. Some of them were smiling. Some were wiping tears away. Nearly all of them where whispering words that sounded like a prayer, or song. But the words they were reciting, in this beautiful garden, in Shiraz, in Iran, weren’t the words of the Koran. The words they were reciting were the words of a poet born in Shiraz 700 years ago called Hafez. Read more at the Independent.

New Books

The Apothecary’s Heir by Julianne Buchsbaum

[Paperback] Penguin, 80 pp., $18.00

[Paperback] Penguin, 80 pp., $18.00

Poet Julianne Buchsbaum has won acclaim for her “rich, lucid, alliterative lexicon, full of apt surprise” (Reginald Shepherd); “there is something of Wallace Stevens in her precision, her incredible diction,” says Matthew Rohrer. Her new collection, The Apothecary’s Heir, depicts a damaged world in which the speaker is trying to make sense of human relationships in the aftermath of loss. A series of meditations on landscapes of our postmodern world—a sickbed, a gas station, a bomb shelter, a rest stop along a highway—these supple poems explore the frailty of human connectedness and anatomize desire in a world of pharmaceuticals and microchips.

Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus: A Biography by Lisa Jarnot

[Hardcover] University of California Press, 550 pp., $39.95

This definitive biography gives a brilliant account of the life and art of Robert Duncan (1919-1988), one of America’s great postwar poets. Lisa Jarnot takes us from Duncan’s birth in Oakland, California, through his childhood in an eccentrically Theosophist household, to his life in San Francisco as an openly gay man who became an inspirational figure for the many poets and painters who gathered around him. Weaving together quotations from Duncan’s notebooks and interviews with those who knew him, Jarnot vividly describes his life on the West Coast and in New York City and his encounters with luminaries such as Henry Miller, Anais Nin, Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin, Paul Goodman, Michael McClure, H.D., William Carlos Williams, Denise Levertov, Robert Creeley, and Charles Olson.

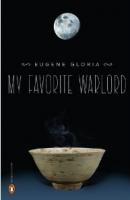

My Favorite Warlord by Eugene Gloria

[Paperback] Penguin 96 pp., $18.00

[Paperback] Penguin 96 pp., $18.00

The themes of identity, relationships, and the poet’s sense of origin are at the heart of Eugene Gloria’s rich and captivating new collection. The title poem weaves together Japan’s sixteenth-century warlord Hideyoshi with a meditation about the poet’s father’s dementia; “Here on Earth” embraces post-racial America and the speaker’s own sense of displacement in the Midwest. In elegy and psalm, as well as ancient forms from Asia such as the haibun and pantoum, these elegant and passionate poems enact rage, civility, love, travel, and art as well as explore Gloria’s own fears of frailty and erasure.

I Came, I Saw: Eight Poems by John Peck

[Paperback] Shearsman Books, 118 pp., $17.00

“For my money, the best poet of my generation. . . as indifferent to academic fashions as he is to those of the poetry market.” —Clive Wilmer

Recent Reviews

Poetry May-September 2012: 56 Works from Trethewey, Plumly, Shaughnessy, & More

by Barbara Hoffert

“No matter how much za’atar you eat/ you still gotta work to be an/ Arab/writer/woman.” I love that line, actually a section title from Laila Halaby’s My Name Is on His Tongue, a poetry collection out this month from Syracuse University Press. You’ll soon see a starred review in Library Journal (and elsewhere, I bet), but one of my great frustrations as poetry editor is that I cannot manage to review all the good books that come my way. Hence my periodic poetry roundups, framing the possibilities for interested readers. This roundup covers summer titles (May 2012–September 2012); surely, pop fiction isn’t the only good beach reading around.

Read more at Library Journal.

Dear America: How Allen Ginsberg’s Letters Were an Extension of His Poetry

by Adam Kirsch

Reading The Letters of Allen Ginsberg is an unexpectedly moving experience. It is unexpected because, 11 years after the poet’s death and some 50 years since he wrote his major poems, “Howl” and “Kaddish,” there can be few readers who have not already decided how they feel about Ginsberg—whether they love him, with the special ardency he inspired in his disciples, or whether they disdain him, as so much of the American literary establishment, and especially its Jewish subdivision, did and does. Beat saint or master self-promoter, modernist innovator or post-literate sloven, prophet of liberation or glorifier of drugs and crime: the battle lines around Ginsberg have been drawn for several generations. Yet his letters show that, even if every count in the indictment is true, there was something rare and genuine about Allen Ginsberg. He may have been a fool, but he was a holy fool; and next to his holiness, the maturity and realism of his critics can look a bit unlovely. Read More at Tablet Magazine.

Correspondences

Derek Walcott: ‘”The Oxford poetry job would have been too much work”

by Stephen Moss

by Stephen Moss

The battle to become Oxford professor of poetry in 2009 was worthy of a mock-heroic poem by Alexander Pope. First, the frontrunner Derek Walcott pulled out following a smear campaign that disinterred allegations of sexual harassment dating back to the 1980s and 90s. Then the eventual victor, Ruth Padel, had to resign after less than a fortnight, when she was implicated in the smear. It was an ugly business, but it did get poetry – that most marginalised of literary forms – on to the front pages for a while. Read more at the Guardian.

Conversation: Poet Natalie Diaz

by Mary Jo Brooks and Jeffrey Brown

Natalie Diaz grew up on the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation on the border of California, Arizona and Nevada. She left the reservation to play basketball for Old Dominion University in Virginia and later for professional leagues in Asia and Europe. While she was in college, she also began to write poetry. Her first collection of poems, When My Brother Was an Aztec, has just been published. Many of Diaz’s poems deal with the harsh realities of reservation life: poverty, teen pregnancy and meth-amphetamine drug addiction. Read more at the PBS NewsHour.

Broadsides

Visionary Kitsch: Concretism vs. Surrealism in Brazil

by Lucas de Lima

by Lucas de Lima

In light of the prominence of internationally recognized figures such as Octávio Paz, Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo, and Aimé Cesaire, it is undeniable that surrealism has long enjoyed a rich and fruitful trajectory in Latin American poetry written in Spanish, French, and even Vallejo’s native Quechua[1]. As soon as one turns to the literature of Portuguese-speaking Brazil, however, the influence of André Breton and countless writers and artists worldwide seems either lacking or, upon further consideration, mysteriously obfuscated. Read more at Montevidayo.

Lucrezia Borgia’s Hair and Forgotten Names

Walter Savage Landor can write a memorable poem about almost anything.

by Robert Pinsky

Sometimes a poem thrills with a subject that might have seemed slight, or unlikely, or impossible. Some poets give the feeling they can make a memorable poem about anything at all. For this month’s Classic Poem, here are a couple of examples, involving aristocratic shoplifting and senile memory loss. Read more at Slate.

Deus in Machina: Poetic Technique in Derek Walcott’s Omeros

by Andrew Singer

Much has been written about Derek Walcott’s epic book-length poem, Omeros, since its publication in 1990 — deservedly so — but little has been attempted of direct poetic analysis. Poetry, especially formal verse, spans a territory that borders music on one side and meaning on the other. A masterful poet unfolding verse is keenly attuned to both, exploring and playing on their interrelation in continually surprising ways. Recognizing this interplay between sound and sense is one of the great refined pleasures of reading an accomplished poem. Suffusing every part of Omeros, regardless of action or complexity, philosophical meaning or depth of thought, is its music. To get at this most directly, let us examine a section where nothing special happens, where no particularly overarching complexity of meaning will distract. Read more at Open Letters Monthly.

My Marianne Moore

Modernist master as stealth weapon.

by Maureen N. McLane

She has no heirs. She has several epigones but their detail-laden lacquered ships for me don’t float. She flares singular, exemplary, a diamond absolute the American East forged in a pressure chamber we have yet fully to excavate. Read more at the Poetry Foundation.

Drafts & Fragments

The Poetry Station

The Poetry Station is a freely accessible, web-based video channel and portal for poetry created by the English & Media Centre from a small grant from Arts Council of England.

Plinko Poetry

Plinko Poetry is a new interface for electronic poetic expression, by Inessah Selditz and Deqing Sun, two Master’s students at NYUs Interactive Telecommunications Program. The installation draws source text from current @nytimes and @FoxNews tweets and creates a new corpus of ever-changing poetic text based on the zeitgeist of current headlines.

Plinko Poetry is a new interface for electronic poetic expression, by Inessah Selditz and Deqing Sun, two Master’s students at NYUs Interactive Telecommunications Program. The installation draws source text from current @nytimes and @FoxNews tweets and creates a new corpus of ever-changing poetic text based on the zeitgeist of current headlines.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Poetry Prize Culture and the Aberdeen Angus

by Peter Riley

by Peter Riley

In January the poet John Burnside won the T.S. Eliot Prize with his book Black Cat Bone. Three months earlier he won the Forward Prize with the same book. These are the two most prestigious and financially rewarding poetry prizes in the country. Burnside has now gained twelve literary prizes (of which four are for books of prose) since his first collection won the Scottish Arts Council Book Award in 1988. That’s not counting short-listing. But short-listing for prizes like these does count: it is added to the honours list and furthers all aspects of the career. The total of Burnside’s awards including these is nineteen. This is what poetry prizes are like in U.K. – they tend to come in convoys. Read more under Poetry Notes at Fortnightly Review.

This is an interesting article on the nature and value of poetry prizes, which is something that I have wrestled with in the past, having run three poetry-book competitions over a span of twenty-two years. I need to say first that there is much marketing value associated with winning or (from the publisher’s standpoint) awarding a prize. That being said, how, really, do we make decisions about the “best” or the most deserving except as a subjective judgment? The answer is: we don’t. It is one thing to say, as I mentioned to a friend the other week, “You should take a look at Lucia Perillo’s work; I think you would like it,” and another to say that it conforms, by whatever qualifications, to a level of excellence that is, by implication, superior to another. As the article states, this has something in common with judging prize livestock. When we settle for the shortcut that is a judge’s choice, we inevitably begin to make other connections (Does my appreciation for the judge’s work color my appreciation for the work at hand? How could she have chosen this? ) to the detriment of our own very personal response to the poetry. And so the poetry begins to move away from its purpose and potential, or rather by involving ourselves in the judging process, we begin pushing it away. Either way, I can’t help thinking the loss is ours.

—David Sanders