October 14, 2015

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

1536 – Garcilaso de la Vega, Spanish poet/diplomat, dies in battle.

1565 – Thomas Chaloner, English statesman and poet (b. 1521), dies.

1619 – Samuel Daniel, English poet (b. 1562), dies.

1637 – Gabriello Chiabrera, Italian poet (b. 1552), dies.

1703 – Thomas Hansen Kingo, Danish poet (b. 1634), dies.

1864 – Maurice de Plessys, French poet (Palace Occidental), is born.

1867 – Masaoka Shiki, Japan, haiku & tanka poet/diarist (Salt Water Ballads), is born.

1880 – Otto V Ekelund, Swedish poet/writer (Sak och sken), is born.

1894 – E.E.Cummings (Edward Estlin), Cambridge Massachusetts, poet (Tulips & Chimneys), is born.

Summer sky

clear after rain—

ants on parade

—Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902)

“Summer sky / clear after rain— / ants on parade” —Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902)

World Poetry

Les Murray: the People’s Nobel Winner

In the late 1900s, no international poetry festival was complete without the presence of at least one (and occasionally, all) of what we younger poets called, only half-jokingly, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Joseph Brodsky and Les Murray. By the end of the century three had received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Surprisingly, the odd man out was Les Murray.

UK’s Anvil and Carcanet Presses to Merge

Two of the UK’s most important independent literary publishers, Anvil Press Poetry and Carcanet Press, have announced a merger that will relocate Anvil’s operations from Greenwich to Carcanet’s Manchester base. This will create “the most diverse world poetry list in the United Kingdom, and one of the great poetry lists in the Anglophone world,” according to the announcement on the move.

Les Murray is the only member of the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” not to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Recent Reviews

Henri Cole’s Nothing to Declare

by Joseph Spece

Few things embolden the iconoclast like punditry’s insistence on singing mediocrity. Like recent books by Louise Glück (whose Faithful and Virtuous Night won the National Book Award in 2014) and Gregory Pardlo (whose Digest won the Pulitzer Prize in 2015), Henri Cole’s Nothing to Declare is recommended by all the Establishment’s proper nodders, but does not contain vital, fought poems. Tidy poems, sure; pat little boxes of words, yes; poems to wrap a hearty ‘Hmmmmph’ around; but never poems fit to meet—or be—the Gorgon.

Mediators! Matadors! Joshua Clover’s ‘Red Epic’

by Jon Curley

A swansong for the millennium has just been written and none too soon; or rather, an evensong for late capitalism’s annihilation. The unlikely form for this enthusiastic apocalyptic message is poetry and, against all expectations, given the usual banality of so much politically charged literature of recent memory, it succeeds powerfully. Joshua Clover’s Red Epic is an epic of fiery vision and uncommonly strident radical critique out of keeping with comparable voices of discontent. If you are disgusted by current global conditions and drawn to intelligent work densely layered with surprising juxtapositions of historical reference, statement, and prophecy, then you will find Red Epic revelatory. You will also probably wish to abide some of its more extreme commands or be convinced of their theoretical worthiness — as when one poem implores the reader to “seize the fucking banks.”

Inventing the New and Selected: Review of The Nerve of It by Lynn Emanuel

by Jennifer Kwon Dobbs

At midcareer, usually after publishing a fourth book, a poet will step back and consider the entirety of her work, evaluating individual poems’ significance to the unfolding arc of her artistic vision. Holding this mirror up, the poet will then compile a chronological “best of” selected from previous collections resulting in a retrospective of her past and current modes.

How interesting is this ritual for the poet presiding over it and for the reader receiving it? Though a new and selected volume is both a career achievement and a milestone, it’s still a book of poems, and so it risks, as with any book, rehearsing expected gestures. For critically acclaimed poet Lynn Emanuel, “a book of poems is a damn serious affair” just as it was for Wallace Stevens. She possesses too original and restless an intellect merely to dust off the tried and true within her oeuvre and tidy it up with a table of contents.

The Timely Anxiety of Linda Gregerson’s Prodigal

Anxious, dizzyingly ambitious, and fiercely beautiful, her work forces readers to interrogate their own vulnerabilities and failings.

by Garth Greenwell

Linda Gregerson’s new volume of selected poems, Prodigal, gathers work from nearly 40 years of a career as remarkable as any in contemporary American poetry. The pleasures of such a retrospective are the pleasures of long acquaintance, and with Gregerson, those pleasures are both sensual and intellectual. The poems’ gorgeousness of sound and image is checked by a ferocious, sometimes acerbic, always morally demanding intelligence, at once plangent and analytic. Her characteristic poems make use of diverse materials—the story of a current event, a recounting of literary or historical antecedent, the emotional ballast of private life—yoked together through associative leap and juxtaposition. Gregerson’s interests range from Saint Augustine to the genome; she is one of only a few poets working in America today with a genuine interest in science. Rather than strict meter or rhyme, it’s argument—what she calls “the longing-for-shapeliness”—that gives her poems their form.

Broadsides

John Clare's Heirs

The Enduring Reach of a Rural Poet

by Stephen Burt

Probably nobody wishes they had been John Clare. The son of an agricultural laborer and an illiterate mother in tiny Helpston, Northamptonshire, Clare (1793–1864) had only the barest schooling. After finding, at age thirteen, “a fragment” of James Thomson’s long poem The Seasons (1730), Clare “scribbled on unceasing,” drafting his own poems in fields and ditches. Helped by a vogue for peasant poets, his Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery (1820) likely sold more than 3,000 copies in a year. Visits to London literati, and three more books, ensued, despite diminishing sales. In 1832 Clare, his wife, and their six children left Helpston for another village, a few miles off, where he never felt at home. Five years later Clare was declared insane and confined to an asylum. In 1841 he escaped and walked home, sleeping under culverts and trudging twenty miles a day. Clare spent the rest of his life in another asylum, “disowned by my friends and even forgot by enemies,” though in some years he continued to write. At times he thought he was Lord Byron. His late poems can present a scary sense of disembodied, empty confusion.

Most Overrated Writers #1: Frederick Seidel

By Brooke Clark

Frederick Seidel is the rare case of a writer who became less interesting as he became more himself. His first (and best) book, Final Solutions (1963), contains some remarkable poems, but is so heavily under the influence of Robert Lowell that Seidel could almost be said to be ventriloquizing the older poet (“To My Friend Anne Hutchinson” is the most obvious, but far from the only, example). There was a long pause before his second book, Sunrise (1979), by which time Seidel had found his own voice. Without the Lowellesque trappings, however, his poems appear not just bare, but barren. They deal with travelling, hotels and restaurants, motorcycles, and his experiences in what might be called “society,” but, in contrast to the excitement of Final Solutions, the experience of reading Sunrise is one of overwhelming tedium.

Li Po’s Restless Night: Improvisations on a Theme

by Joe Linker

Florence showed me what she called the most famous of Chinese poems. She had made her own translation from a Chinese language newspaper clipping. The poem was accompanied by a cartoon-like drawing of a man lifting up from a cot, the moon in his face and eyes, the moonlight coming through an open window and shining on the cot and a bedroom floor. Florence explained the poem to me, and wanted me to help her work on her translation of the poem into English, and we enjoyed sharing language lessons. For some time after I left the school, I kept in touch with Florence, but it’s been many years now. I used to hear from her every Christmas; she would send me a long, handwritten letter in impeccable penmanship and flawless English grammar, and usage and sentence structure, and ask me to “correct” the writing for her.

Auden's Spell

by Sean O'Brien

WH Auden concludes his great poem “In Praise of Limestone” (1948): “when I try to imagine a faultless love / Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur / Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.” This geological attachment had a long history. As a boy, Auden (1907-73) had acquired books about mining and engineering. As well as being absorbed by the technicalities of the subject, he also viewed mining machinery and mining landscapes as having a magical or religious significance, and this sense of things remained with him for the rest of his life. On the wall of his workroom at Fire Island near New York, he displayed a map of Alston Moor in the north Pennines, and he was later to revisit the region. Many poets have a founding myth of place to animate and sustain their writing. Dante in exile had the city of Florence, Wordsworth had the Cumbrian lakes and Seamus Heaney had the bogland of rural County Derry. Auden’s myth was located among the fells and lead-mines.

Frederick Seidel is the rare case of a writer who became less interesting as he became more himself.

Drafts & Fragments

UK's Largest Poem Unveiled on Royal Mile Banner

A huge banner displaying what is believed to be the UK's largest printed poem has been unveiled on Edinburgh's Royal Mile. Spiral, by Elizabeth Burns, has been reproduced on a 25 by eight metre sign to mark National Poetry Day today and will remain in place on the famous street until next summer. The poet, who was a descendant of the family of Robert Burns, died in August aged 57 and her family said it was a poignant moment when they saw her work displayed on the poster for the first time this morning.

A huge banner displaying what is believed to be the UK’s largest printed poem has been unveiled on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.

Poetry In the News

Poet Simic Cherishes N.H. Life with Donald Hall-Jane Kenyon Prize

New Hampshire poet Charles Simic has received many accolades throughout his seven-plus decades of life, including the Pulitzer Prize and the MacArthur Fellowship. On Tuesday night, one more award was added to that list. Simic, 77, received the Donald Hall-Jane Kenyon Prize in American Poetry at the Concord City Auditorium, in front of an audience that turned out to congratulate him and hear his poetry. The Donald Hall-Jane Kenyon prize is co-sponsored by the Monitor and the Concord City Auditorium, with assistance from the Kimball Jenkins Estate. He is the sixth recipient of the award.

The White Privilege of British Poetry Is Getting Worse

Last week, Claudia Rankine’s book, Citizen, won the Forward prize for Best Collection. Rankine, a Jamaican poet living in the US, was the only non-white poet on the shortlist. The list for best first book was more diverse. It may be significant that it is with this particular collection that Rankine broke through to a wider audience. Citizen – with its searing anecdotes of everyday aggression and the murder of black people by white cops, delivered in clear and remarkably restrained prose poems – reflects more directly on racism than her previous books, which were arguably more avant-garde in form and language.

Charles Simic was recently awarded the Donald Hall-Jane Kenyone Prize in American Poetry.

New Books

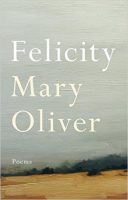

Felicity: Poems by Mary Oliver

[Hardcover] Penguin Press, 96 pp., $24.95

“If I have any secret stash of poems, anywhere, it might be about love, not anger,” Mary Oliver once said in an interview. Finally, in her stunning new collection, Felicity, we can immerse ourselves in Oliver’s love poems. Here, great happiness abounds. Our most delicate chronicler of physical landscape, Oliver has described her work as loving the world. With Felicity she examines what it means to love another person. She opens our eyes again to the territory within our own hearts; to the wild and to the quiet. In these poems, she describes—with joy—the strangeness and wonder of human connection.

Selected Poems by John Updike

[Hardcover] Knopf, 320 pp., $30.00

Though John Updike is widely known as one of America’s greatest writers of prose, both his first book and his last were poetry collections, and in the fifty years between he published six other volumes of verse. Now, six years after his death, Christopher Carduff has selected the best from Updike’s lifework in poetry: 129 witty and intimate poems that, when read together in the order of their composition, take on the quality of an unfolding verse-diary. Art, science, popular culture, foreign travel, erotic love, the beauty of the man-made and the God-given worlds—these recurring topics provided Updike ever-surprising occasions for wonder and matchless verbal invention. His Selected Poems is, as Brad Leithauser writes in his introduction, a celebration of American life in the second half of the twentieth century: “No other writer of his time captured so much of this passing pageant. And that he did so with brio and delight and nimbleness is another reason to celebrate our noble celebrant.”

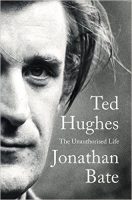

Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life by Jonathan Bate

[Hardcover] Harper, 672 pp., $40.00

Ted Hughes left behind a more complete archive of notes and journals than any other major poet, including thousands of pages of drafts, unpublished poems, and memorandum books that make up an almost complete record of Hughes's inner life, which he preserved for posterity. Renowned scholar Jonathan Bate has spent five years in the Hughes archives, unearthing a wealth of new material. His book offers, for the first time, the full story of Hughes's life as it was lived, remembered, and reshaped in his art. It is a book that honors, though not uncritically, Hughes's poetry and the art of life-writing, approached by his biographer with an honesty answerable to Hughes's own.

The Emperor of Water Clocks: Poems by Yusef Komunyakaa

[Hardcover] Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 128 pp., $23.00

"If I am not Ulysses, I am / his dear, ruthless half-brother." So announces Yusef Komunyakaa early in his lush new collection, The Emperor of Water Clocks. But Ulysses (or his half brother) is but one of the beguiling guises Komunyakaa dons over the course of this densely lyrical book. Here his speaker observes a doomed court jester; here he is with Napoleon, as the emperor "tells the doctor to cut out his heart / & send it to the empress, Marie-Louise"; here he is at the circus, observing as "The strong man presses six hundred pounds, / his muscles flexed for the woman / whose T-shirt says, these guns are loaded"; and here is just a man, placing "a few red anemones / & a sheaf of wheat" on Mahmoud Darwish's grave, reflecting on why "I'd rather die a poet / than a warrior."

Clayfeld Holds On by Robert Pack

[Paperback] University Of Chicago Press, 112 pp., $18.00

In Clayfeld Holds On, Robert Pack offers his readers a comprehensive portrait of his longtime protagonist Clayfeld, who is also Pack’s doppelgänger, his alternate self, enacting both the life that the poet has lived and the life he might have lived, given his proclivities and appetites. Poet and protagonist, taken together, are self and consciousness of self, the historical self and the embellished story of that literal self.

If I have any secret stash of poems, anywhere, it might be about love, not anger,” Mary Oliver once said.

Correspondences

Wayne Koestenbaum with Phillip Griffith

On September 21st at The Kitchen, Wayne Koestenbaum performed a suite of trance-like Sprechstimme improvisations at the piano to mark the publication of his new book, The Pink Trance Notebooks, a series of poems assembled from a yearlong experiment in journaling (Nightboat, 2015). In the most rousing of these songs, Koestenbaum intoned praise for having his tubes tied at Duane Reade—all set to a piece by Chopin. The week before this performance, Koestenbaum, whose seventeen other books include volumes of criticism, poetry, and a novel, sat down with Phillip Griffith in his Chelsea studio to discuss poetry and painting, trance, the French language, and “fag ideation.”

The Wisdom of Professor Z

by Tom Bennett

Earlier this year, I interviewed Benjamin Zephaniah – one of Britain's best contemporary poets, writers and performers – at Brunel University, where he teaches creative writing and English. The focus of our meeting was meant to be Black History Month, but it quickly broadened out to include the cultures that surround that discussion. Normally, when you meet someone for an interview, you load up with questions in case the conversation doesn't deliver. That wasn't an issue with Zephaniah, who spoke eloquently and forcefully for an hour; I would have happily stayed for several hours more. A fascinating, persuasive man.

Benjamin Zephaniah is one of Britain’s best contemporary poets, writers, and performers.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Lessons from the Past: Timothy Steele

"The only novelty sure to last in poetry is the novelty of talent. Moreover, the alert poet cannot help but be novel: his subjects are the manners and morals and aspects of his world and fellow creatures, and these are always changing. The idea that to be novel, one has to invent a ‘METHOD’ in the Poundian sense is not only wrongheaded: it is unnecessary.”

—from Missing Measures: Modern Poetry and the Revolt against Meter

“The only novelty sure to last in poetry is the novelty of talent.” –Timothy Steele