September 30, 2015

Edited by David Sanders

Specimen Days

1207 – Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi, Persian mystic and poet (d. 1273), is born.

1628 – Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke, English poet (b. 1554), dies.

1899 – Hendrik Marsman, Dutch poet/writer/critic, is born.

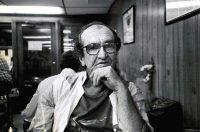

1927 – W. S. Merwin, American poet, is born.

For the Anniversary of My Death

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

—W. S. Merwin

“I will no longer / Find myself in life as in a strange garment / Surprised at the earth” – W. S. Merwin.

World Poetry

RJ Arkhipov Works With His Own Blood to Protest Ban On Gay Donors

Over the decades, many writers have taken inspiration from the celebrated words of Ernest Hemingway: "There is nothing to writing; all you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed." For RJ Arkhipov, a 24-year-old Welsh poet living in Paris, France, however, Hemingway's statement was less of a metaphorical reflection, and more of a proscription. Arkhipov, whose poetry deals with nostalgia, gender, sexuality, friendship, love, travel, and nature, was inspired to present his work written in his own blood.

A Russian Poet Is Celebrated in Scotland, a Land He Never Saw

Poetry has been a part of life in Earlston since the days of Thomas the Rhymer, a 13th-century bard who, according to legend, could foresee bloody battles, royal deaths and even the union of Scotland’s and England’s thrones. But not even Thomas could have predicted that this small village, in a lush Scottish valley, would one day lay claim to one of Russia’s greatest poets: Mikhail Lermontov.

Arkhipov, whose poetry deals with nostalgia, gender, sexuality, friendship, love, travel, and nature, was inspired to present his work written in his own blood.

Recent Reviews

Review: In ‘I Must Be Living Twice’ and ‘Chelsea Girls,’ Eileen Myles Ruminates

by Dwight Garner

“I had always figured if I had a book I’d want my face all over it,” the narrator of Eileen Myles’s autobiographical cult novel “Chelsea Girls” (1994) thinks to herself at a party for one of her early poetry collections. She’s again got her wish. A reissue of “Chelsea Girls,” a coming-of-age story in part about the author’s sexuality (“You said I made being a lesbian look all right,” her narrator comments), has on its cover a striking black-and-white photograph of Ms. Myles taken in 1980 by Robert Mapplethorpe. Androgynous, defiant, perhaps a bit glassy-eyed, she resembles the young Mick Jagger as merged with Cat Power.

Book Review: Domestic Garden by John Hoppenthaler

by Kevin Dublin

John Hoppenthaler is an American poet, professor, and editor. Domestic Garden is his third collection of poetry. His first two collections Lives of Water (2003) and Anticipate the Coming Reservoir (2008), both also published as a part of the Carnegie Mellon Poetry Series, proved Hoppenthaler as a poet who is capable of taking personal moments and through beautiful lyric force and distillation, making them into persona poems that are a part of the deep waters of our collective human consciousness. This third collection uses gardens as a larger metaphor, but the poems are still, as Dorianne Laux writes, “poems of place and witness … [which] ripen necessarily—born out of what they contain, a twice-rich harvest.”

40 Sonnets Review – The Perfect Vehicle for Don Paterson’s Craft and Lyricism

by Sarah Crown

Don Paterson has a thing for sonnets. Back in 1999 he brought out an anthology of 101 of his favourites, and in 2012 he delved deeper into their history with Reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets, a passionate, personal response to the great man’s form-defining sequence. Nor has he confined himself to curation and criticism: in 2006, he produced a warm, responsive reworking of Rilke’s 55-sonnet cycle, Orpheus, while his original collections are punctuated by his own efforts, some of which (such as Landing Light’s superlative “Waking with Russell”) count among his finest poems. “The square of the sonnet exists for reasons which are almost all direct consequences of natural law … and the grain and structure of the language itself,” he said, attempting to explain the form’s abiding appeal – and his own fascination with it – in an article in this newspaper. “Or to put it another way: if human poetic speech is breath and language is soapy water, sonnets are just the bubbles you get.”

Writing the Black Terrific

by Carmen Giménez Smith

Race is potentially the most salient matter in American discourse, and contemporary poetry has started to get the message. Many poets and critics have been honest about the exclusionary hegemonic lyric position of the late nineties and early twenty-first century, when many aesthetic movements came and went, but very few considered the paradoxical identity of the othered, including the person of color.

In Ruins

by Jonathan Farmer

Adamic and inhuman, scientific language can feel strangely ambivalent. At least aspirationally (and often actually), it’s the language of objectivity, things as they are, an emblem of knowledge that is more than human, discovered and described by methods and tools that use our human faculties and ingenuity to reach beyond the limitations of our bodies and minds. At the same time, it’s also a sign of human intervention, a reminder that anything we can think of has been humanized by that thinking. Scientific language carries in it a record of our aspirations, our desire to be more or other than human (a particularly human tendency), our hunger and history and subjectivity audible in the language’s attempt to go out into the world unmarked by history, sterile, disinterested in everything it beholds. That conflict plays a fundamental role in David Baker’s 10th collection of poems, Scavenger Loop.

A Queer Excess: the Supplication of John Wieners

by Nat Raha

The poetry of John Wieners is lyric, bold, shameless. It is a poetry of dereliction in the face of the artist’s almost religious devotion to verse and its inherent magic. His early work—the era between The Hotel Wentley Poems (1958) to Ace of Pentacles (1964)—swings with blues and sexual desire, the glamour of drugs and counter-cultures, gay subculture, celebrities and starlets, and tarot, all sources to feed his magical art. Wieners’s work in subsequent years contends with romantic loss and poverty, juxtaposed with moments of pleasure in sexual and gender transgression, and a political awakening in the face of state harassment and psychiatric incarceration.

New Collections from Enzensberger and Jan Wagner

by Ian Pole

Two orders of magnitude, you might say: Enzensberger, born in 1929, who has bestrode German poetry since the late 1950s, who was associated with Boll and Grass in Group 47, who grew up in the west, but were fiercely critical of it. And Jan Wagner , born in Hamburg in 1971, who has won more prizes in Germany than you can shake a stick at, though not the same ones as HME, apparently. Both these poets have translated the poetry of other languages into German; HME most famously in the anthology Museum der modernen Poesie (Museum of Modern Poetry) in which he introduced German readers to a range of modernist writing from William Carlos Williams to Fernando Pessoa. Wagner has translated a range of contemporary British and American poets, including Charles Simic and Simon Armitage.

Roll Deep by Major Jackson

by J. Mae Barizo

There is an irrepressible spirit of voyage in Major Jackson’s newest book, Roll Deep. The title itself alludes to a rocking back and forth, a voyage that moves seamlessly from the past to the present. The entire book—set in destinations as disparate as East Kenya, Greece, Philadelphia—is in itself a reverse voyage, the author working back through the past while simultaneously forging new journeys, both physical and emotional. With a modern yet lyric sensibility, the poems in Roll Deep are a testament both to memory and renewal; the human ability to persevere.

It is a poetry of dereliction in the face of the artist’s almost religious devotion to verse and its inherent magic.

Broadsides

The Shock Absorber

The Griffin Poetry Prize's Ties to a Saudi Arms Deal

by Michael Lista

There is a circle and there is a line.

I'm in the line, queued in a posh Toronto neighbourhood between the man who just lost the race to be Prime Minister, and the country's most powerful newspaper magnate. In line with us are writers, journalists, socialites, industrialists, all wending their way through the warm June evening to be received by Scott Griffin, the redoubtable patron, founder and host of one of the world's richest literary awards, The Griffin Poetry Prize. Tonight is the annual Awards Gala, an opulent celebration of the written word at which Mr. Griffin will award two writers $65,000 each for having authored a winning book.

Hating the Other Kind of Poetry

by Robert Archambeau

1. This is not a how-to guide

It isn’t quite a how-not-to guide either, but I suppose that’s closer.

2. “What you should be doing,” or: the limits of disinterest

A few years ago, when the Conceptualist poet Kenneth Goldsmith was making big waves in the little demitasse cup of the American poetry world, I wrote an essay that tried to explain what his work had to offer and what it didn’t. The email I received in response was gratifying in quantity, if bewildering in content. I’d tried merely to describe Goldsmith’s work, but I found I was condemned for having praised him, praised for having condemned him, praised for having praised him, and condemned for having condemned him—all in roughly equal measure.

Something Borrowed

Kenneth Goldsmith’s poetry elevates copying to an art, but did he go too far?

by Alec Wilkinson

To appreciate the beleaguered position that Kenneth Goldsmith finds himself in, you have to know that in 1997 or 1998 three avant-garde poets, one of them Goldsmith, drinking in a basement bar in Buffalo during a blizzard, decided to start a revolutionary poetry movement, one that went on to endorse “uncreative writing,” a phrase and a field that Goldsmith invented.

Make Song of Them

by Alfred Corn

Charles E. Merrill, founder (with his friend Edmund C. Lynch) of the famous brokerage firm, probably never read this comment by President John Adams: “I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.”

One of the world’s richest literary awards, The Griffin Poetry Prize.

Drafts & Fragments

Prufrock, Lewinsky, and the Poetry of History

How T. S. Eliot’s lovelorn classic still sways us.

by Austin Allen

One of the more striking literary essays in recent memory appeared this summer to zero fanfare. That in itself is no surprise: most literary critics could reveal the nuclear codes without even the NSA noticing. Still, you might have expected some buzz around a splashy Vanity Fair tribute to “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” penned by a longtime fan named Monica Lewinsky.

One of the more striking literary essays to tribute Prufrock, Lewinsky, and the Poetry of History.

Poetry In the News

Here’s the American Poet Pope Francis Just Quoted

Pope Francis cited a Midwestern poet when urging U.S. bishops to welcome Hispanic immigrants into their churches Wednesday. In a particularly poetic passage of a speech at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle, the pontiff noted that his native Argentina—like America—received the Gospel from missionaries. “I am a native of a land which is also vast, with great open ranges, a land which, like your own, received the faith from itinerant missionaries,” he said.

Ted Hughes Poem 'Inspired by row with Sylvia Plath shortly before she died'

The poem written by Ted Hughes about the night his first wife, the poet Sylvia Plath, died was inspired by a row the couple had about her leaving the country, according to a biography. The poem, entitled Last Letter, was unearthed by Melvyn Bragg for the first time in 2010 and describes what happened during the three days leading up to Plath’s suicide in February 1963.

Pope Francis cited a Midwestern poet when urging U.S. bishops to welcome Hispanic immigrants into their churches.

New Books

Erratic Facts by Kay Ryan

[Hardcover] Grove Press, 128 pp., $24.00

At once witty and melancholy, playful and heartfelt, Ryan examines enormous subjects—existence, consciousness, love, loss—in compact poems that have immensely powerful resonance. Sly rhymes and strong cadences lend remarkable musicality to her incisive wisdom. While these pieces are composed of the same brevity and vitality that has characterized her singular voice over the course of more than 20 years, her mind is sharper than ever, her imagination more eccentric and daring. Erratic Facts solidifies Ryan’s place at the pinnacle of American poetry, and proves that she will remain among the leading innovators in literary history.

Supplication: Selected Poems by John Wieners

[Hardcover] Wave Books, 216 pp., $30.00

Supplication: Selected Poems of John Wieners gathers work by one of the most significant poets of the Black Mountain and Beat generation. Includes poems that have previously never been published, the full text of the 1958 edition of his influential The Hotel Wentley Poems, plus poems from rare sources, facsimiles, notes, and collages by Wieners. An invaluable collection for new and old fans.

Errata by Lisa Fay Coutley

[Paperback] Southern Illinois University Press, 88 pp., $15.95

Lisa Fay Coutley’s lyrical debut collection, Errata, investigates the delicate balance between parent and child, love and loss, hope and grief. Errata’s narrator reflects on struggles and fears that span generations in compositions that are at once musical and bleak. Coutley’s narrative journey is often a dark one, exploring not only the loss of loved ones but also the potential to lose one’s very self. The collection unravels the lingering consequences of abuse and addiction, yet threads of hope and determination weave a finely wrought path through the dark side of human relationships, illuminating the power of the will to survive. Coutley’s sharp yet tender collection will both haunt readers and move them to reflect, to remember, and most of all, to persevere.

And His Orchestra by Benjamin Paloff

[Paperback] Carnegie Mellon, 80 pp., $15.95

In his second collection, Benjamin Paloff examines how we relate to others by relating to ourselves, and vice-versa—how the speech that runs through our heads as we run errands, wash the dishes, or brush our teeth is always and inescapably in conversation with those to whom we owe an unpayable debt. In poems that orchestrate imaginal dialogues with absent friends, And His Orchestra traces the inner experience of attachment, intimacy, and separation.

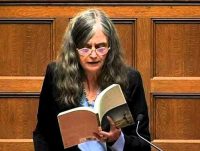

Know Thyself by Joyce Peseroff

[Paperback]Carnegie Mellon, 88 pp., $15.95

Joyce Peseroff’s new collection teases the nature of self-knowledge from a world where identity is fluid, character fragmented, landscape overwhelmed, and culture riven. In poems that dramatize politics, eros, myth, and mortality, Peseroff’s edgy wit cuts through the classical Greek definition—“You’re not an animal/or a god, take the middle path”—to parse our century’s slippery dialectics. Playful and complex, Know Thyself distills music from the salt of human experience.

Poems that dramatize politics, eros, myth, and mortality, Peseroff’s edgy wit cuts through the classical Greek definition.

Correspondences

Claudia Rankine

by Lauren Berlant

I met Claudia Rankine in a parking lot after a reading, where I said crazy fan things like, “I think we see the same thing.” She read a book of mine and wrote me, “Reading it was like weirdly hearing myself think.” This exchange is different from a celebration of intersubjectivity: neither of us believes in that . Too much noise of racism, misogyny, impatience, and fantasy to weed out. Too much unshared lifeworld—not just from the difference that racial experience makes but also in our relations to queerness, to family, to sickness and to health, to poverty and wealth—while all along wondering in sympathetic ways about the impact of citizenship’s embodiment. Plus, it takes forever to get to know someone and, even then, we are often surprised—by ourselves, by each other.

The Pitch: Works and Days

by Carming Starnino

Welcome to the Pitch, a biweekly series on Partisan in which writers come clean about their works-in-progress and share an exclusive excerpt. This week, Carmine Starnino talks to U.S. poet A.E. Stallings about her new verse translation, Works and Days, forthcoming with Penguin Classics.

What’s in the pipeline?

I’m translating this self-taught Greek poet named Hesiod who’s gone back to the land.

Maxine Kumin 1925–2014: The Long Approach: A Life in Poetry

by Eleanor Wilner

I think I am going to get personal in this essay, because my subject is a person first, poet next, though the two, in her case, are not separable, and that inability to separate her life from her poems will be very much my subject, as it was hers. I shall call her Max, because that is what I called her. Though my poems are about as different from hers as poems can be, some of her books have fallen apart in my hands from referring back to them, and some of her poems—a memorable line whose music catches home truth, an image that strikes deep—are wound like strong cords of hemp through my memory in such a way that, pull one thread, the whole thing shimmers.

Alice Notley

by Robert Dewhurst

Alice Notley is my favorite living poet. To consider her work, in toto, is to court cerebral and sensory overload. She has published over thirty-five collections of poetry and prose in a career spanning four decades, which together display a bedazzling variety of forms, musics, voices, measures, ideas. A central figure of the New York School’s precocious “second generation,” Notley has lived since 1992 in Paris, France, where she has cultivated an iconoclastic autonomy from any one poetic school or set of associations.

Eileen Myles: "I’m the Weird Poet the Mainstream Is Starting to Accept"

By Jake Blumgart

Eileen Myles seems to come from a New York that no longer exists. Her first reading took place at CBGBs, she lived four floors below Blondie, and contemporaries with Richard Hell, progenitor of the spiky-haired, torn-suit jacket look. Myles moved to New York from Boston in 1974 and, now 65, still spends much of her time in the city (courtesy of a rent-controlled apartment in the East Village). She long outlasted any of the other acts that used to perform at CBGBs, not to mention the club itself, but largely kept to the underground scene and its attendant press houses. Until this week.

Alice Notley’s work is to court cerebral and sensory overload, publishing over thirty-five collections of poetry and prose.

Envoi: Editor’s Notes

Lessons from the Past: W. S. Merwin

"Writing poetry is never a wholly deliberate act over which you have complete control. It’s important to recognize that writing is at the disposition of all sorts of forces, some of which you don’t know anything at all about. You can describe them as parts of your own psyche, if you like, they probably are, but there are lots of other ways of describing them that are as good, or better—the muses, or the collective unconscious. More suggestive and so, in a way, more accurate. Any means of invoking these forces is good, as far as I’m concerned."

—from “The Paris Review,” W. S. Merwin, The Art of Poetry No. 38

Interviewed by Edward Hirsch

Writing poetry is never a wholly deliberate act